Permaculture Cities

Applying Permaculture principles to urban areas

Thursday, September 1, 2016

Regenerative Cities

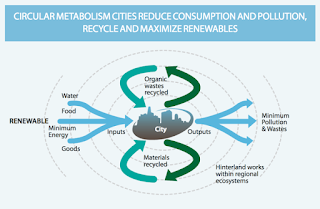

The regenerative city applies ecological principles to urban redevelopment to make the city environmentally viable. It should make the city socially viable as well.

To make the regenerative city, therefore, it’s necessary to reimagine these flows of production and consumption, of transport and construction, through an ecological lens, and then to re-engineer them. This involves remaking the links that once existed between cities and nature (think of the orchards and market gardens that once ringed London), between urban systems and ecosystems.

The regenerative city is more than just being “sustainable.” Ecological debt has already degraded the soils, forests and watercourses that cities depend on. “Sustaining” implies no improvement on this degraded state, just as “carbon neutral” makes no inroads into our carbon debt.

Making the regenerative city (thenextwave)

Saturday, April 23, 2016

Bring Back the Euroloaf

Back in the 1970s a remarkable housing project was built in Toronto; The St. Lawrence neighbourhood has been described by journalist Dave LeBlanc as the “best example of a mixed-income, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly, sensitively scaled, densely populated community ever built in the province”. Designed around principles espoused by Jane Jacobs (some even claim she had a hand in designing it; she didn't), it was a mix of low street facing townhouses and long mid-rise apartment blocks of a relatively consistent height. They looked a lot like buildings from Paris or Scandinavia and were nicknamed “Euroloaf” because they are kind of shaped like loaves of bread.

Friday, October 9, 2015

Urban farming is booming

Pea shoots that have traveled 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) to grace a salad are bound to taste better and be more nutritious, she says, than those that have traveled half a continent or farther. “One local restaurant that I sell to used to buy its sprouts from Norway,” Leadley says. Fresher food also lasts longer on shelves and in refrigerators, reducing waste.

Food that’s grown and consumed in cities has other advantages: During times of abundance, it may cost less than supermarket fare that’s come long distances, and during times of emergency — when transportation and distribution channels break down — it can fill a vegetable void. Following large storms such as Hurricane Sandy and the blizzards of this past winter, says Viraj Puri, cofounder of New York City–based Gotham Greens (which produces more than 300 tons (270 metric tons) of herbs and microgreens per year in two rooftop hydroponic operations and has another farm planned for Chicago), “our produce was the only produce on the shelf at many supermarkets across the city.”

Despite their relatively small size, urban farms grow a surprising amount of food, with yields that often surpass those of their rural cousins. This is possible for a couple reasons. First, city farms don’t experience heavy insect pressure, and they don’t have to deal with hungry deer or groundhogs. Second, city farmers can walk their plots in minutes, rather than hours, addressing problems as they arise and harvesting produce at its peak. They can also plant more densely because they hand cultivate, nourish their soil more frequently and micromanage applications of water and fertilizer.

Urban farming is booming, but what does it really yield? (Ensia)

Friday, August 28, 2015

Urban Vineyards

“Many of those people coming to the city [in the 19th century] knew it was their final destination,” Hortshorn says, a glass of pinot noir in hand. “They weren’t going to go back home, their families they might never see again, but when they saw San Francisco’s vineyards come into view, it was one of the first things that was familiar to them. People forget that this city was home to many vineyards and wines.”Can San Francisco establish its first urban vineyard since the 19th century? (The Guardian)

San Francisco’s wine industry ended following the 1906 earthquake that devastated the city, killing thousands. In an effort to rebuild quickly, vineyards disappeared in favor of residential zoning.

On a small slope in Bernal Heights that is no larger than a basketball court, more than 200 grapevines are proof wine grapes can grow in the city. It doesn’t appear to be much, but it is heading in a good direction. Hortshorn says it takes time to develop vines for the long haul. “When the plants get big enough we will put them up and wire them together and then it will have that true vineyard look,” she says.

Saturday, March 28, 2015

Curbside agriculture

The L.A. City Council has voted to allow Angelenos to plant fruits and vegetables in their parkways - that strip of city-owned land between the sidewalk and the street - without a permit. Fruit trees, however, will still require a permit.

Until now, planting anything other than grass or certain shrubs on that strip required a $400 permit, and homeowners were often fined for not complying. But the ordinance approved Wednesday says people can replace shrubs or grass with edible plants like fruits and vegetables, as long as they follow the city’s guidelines for landscaping parkways.

LA City Council approves curbside planting of fruits and vegetables (KPCC)

Small urban plots

During the World War II the British were encouraged to ‘Dig for Victory’. Garden vegetable plots were at their height and allotment demand peaked. Homegrown produce allowed farmers to focus on grain and dairy production — activities ill suited to small-scale urban plots.

So, what was the contribution of homegrown efforts to the national diet? How effective could it actually have been? Here are the stats: during the World War II, allotments and gardens provided around 10% of food consumed in the UK because of the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign whilst comprising <1% of the area of arable cultivation.

Take a moment absorbing the significance of that statement. Home growing produced ten times the food per acre than arable farms! How can that be? Aren’t we told repeatedly, that we can only feed the world with grains? And that only intensive agriculture can deliver?

Of course it could be argued that farming has become more efficient since WWII. Indeed, with the ‘green-revolution’ of the 50s and 60s intensive inputs, pesticides and high yield varieties increased the efficiency of arable farms, with the biggest impact seen on wheat yield, which increased seven fold. However, recent studies show that intensive farming does not come close to the levels possible from allotment and vegetable gardens.

“More recent UK trials conducted by the Royal Horticultural Society and ‘Which?’ Magazine showed fruit and vegetable yields of 31–40 tonnes per hectare per year (Tomkins 2006), 4–11 times the productivity of the major agricultural crops in the Leicestershire region (DEFRA 2013),” says one paper.

That left me speechless!

So, how is it possible that low-tech vegetable plots out perform modern mechanised farms? Here are two parts of the answer:

Home Growing Produces Ten Times the Food of Arable Farms (Our World 2.0)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)